The Fraser Valley Writers Festival is a free two-day event that took place on November 1 and 2, 2024 at the University of the Fraser Valley’s Abbotsford campus. The festival featured workshops, panelist discussions, and keynote addresses from ten acclaimed Canadian writers. As a literary event that draws in avid readers and aspiring writers, Read Local BC asked all ten authors attending the festival to share one piece of writing advice that has changed their lives or how they write.

Carleigh Baker

Crafting your story’s ending is challenging. One of the most common revision notes we get is, “It needs something more at the end.” But what? So we go to those last few lines and stare at them, wondering what happens next.One of my brilliant editors pointed out that in nearly all my story drafts, those last few lines are usually pretty good. But there’s a little dead space in the paragraphs leading up to the ending that need some filling in, in order for it to really land. This was so helpful for me, since I usually assumed the ending itself needed to be longer. When I started going backwards, it was obvious I had rushed a little to get to that final big moment. There were details I could add to make the lead up more robust. Sometimes plot or character details, but often just sensory details—sights and smells and textures. Carleigh Baker is the author of Last Woman (Penguin Random House Canada, 2024). She will take part in the FVWF’s “Revise” panel discussion on November 2 at 11 am and will lead a short fiction workshop at 10 am on the same day.

Billy-Ray Belcourt

I remember reading on social media once someone saying that no one is truly waiting with bated breath for your new book so there’s no need to rush. It may at first seem pessimistic but back then it was a much-needed reminder to take my time and to be certain that what I was working on was what I really wanted to be working on. Bringing purpose and intention to the writing is always valuable.Billy-Ray Belcourt is the author of Coexistence (Penguin Random House Canada, 2024). Billy-Ray will kick off the festival as a keynote address on November 1 at 7 pm.

Kate Black

Use writing as a tool to figure out what you’re writing about. Every wise instructor and editor I’ve had has offered me some version of this advice throughout my writing career, and it’s always a good reminder. Who wants to hear from someone who had it all figured it out before they started typing, anyway? Kate Black is the author of Big Mall (Coach House Books, 2024).

Adrienne Gruber

A friend once said to me that she never gives unsolicited advice. I love this, especially when it comes to writing practice, because we all get to the finish line in different ways, and there’s no one way to write a book. Everyone’s circumstances are unique, and everyone figures out their own way forward. Realizing that I don’t have to write every morning or designate specific times/days to write has been freeing. I find a lot of advice out there for writers, especially early-career writers, tends to just be blanket statements like ‘write every day’, or ‘read widely’—these vague, nebulous statements that don’t take into account the very real barriers that a lot of writers have. Writing so often happens in the background of daily life, with everything else taking priority. As a teacher and parent of three young kids, I need to fit my writing time and my reading time into the short windows I have in a day. I go for a lot of walks and hikes with my dog, which is essential for my mental health but also take up a lot of the free time I might otherwise have. Adrienne Gruber is the author of Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood (Book*hug Press, 2024).

Richard Kelly Kemick

Update your myspace account as often as possible. I think it’s a fool’s errand to give writing advice because the industry is in a perpetual stage of change. Things that were deemed essential to a writing career can fade abruptly and be overtaken by a new glimmering trend. If someone wants to keep abreast of these trends, it becomes increasingly impossible to have the time and focus required to create anything. The only piece of advice that, I think, is truly worth anything is so obvious it hardly needs stating: write as best as you can as often as you can.Richard Kelly Kemick is the author of Hello, Horse (Biblioasis, 2024).

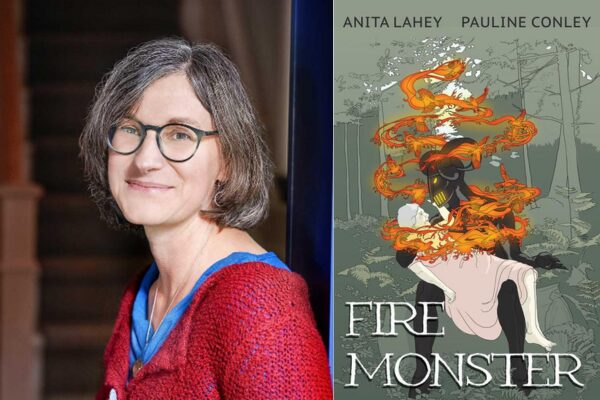

Anita Lahey

My mentor, the late, brilliant Ottawa poet Diana Brebner, told us this during the first poetry workshop I ever took: “No one is out there waiting for you to write this poem.” As with most of her poetry (order The Ishtar Gate (McGill-Queen’s Press) from your local bookseller, I beg you!), many possible meanings pack into this line. For one thing, your impulse to make poems has nothing to do with the world’s expectations of you. If you need to write, you need to write, period. Flip that around. If you’re writing for applause or accolades, you’re likely to be disappointed. (Trust me.) What’s more, your work may suffer. Its very impulse won’t have integrity. So, take seriously this need to write. Treat it with respect. Turn inward to find the poem, setting aside how it might be received, or perceived. But remember: you’re just a person compelled to write a poem. So: get over yourself! No one cares; nor, really, should they. Ironically, it’s when we manage to hold both these contradictory things in balance—taking our work seriously while letting go of our sense of its being “important”—that we might (stress might) make something that really does matter: something human, something true. Also, it’s way more fun to write this way. Anita Lahey is the author of While Supplies Last (Vehicule Press, 2024) and Fire Monster (Palimpsest Press, 2024).

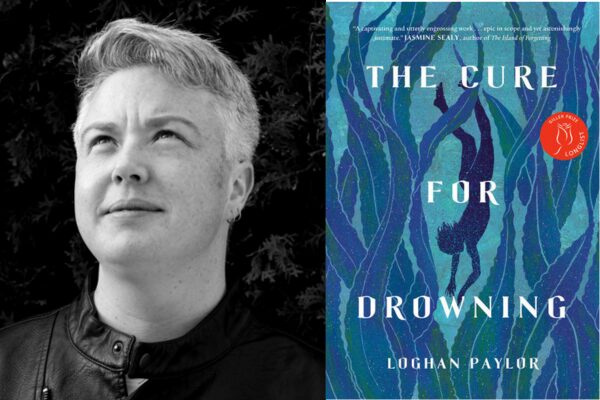

Loghan Paylor

The piece of advice that fundamentally changed how I approach my writing was hearing “a first draft is just you explaining the story to yourself.” Even when writing alone, I had often felt very exposed, whether out of fear of judgment, disappointment from comparing raw drafts to polished work, or inner perfectionism. With all of that hanging over my head, I felt as though every word that ended up on the page had to be just right. It was paralyzing.Now when I’m in the early stages of a new project, I prioritize giving myself space and privacy to get messy and make mistakes, without worrying about how it’s all going to come together. I write longhand in cheap notebooks, with my phone in airplane mode and my computer turned off. Knowing that no one else will ever see those notebook drafts has done so much to build trust in my process. I am learning that beginnings are almost always awkward and ugly, that most of the magic happens during revisions, and that I never quite know where an idea is going to lead until I let it.Loghan Paylor is the author of The Cure for Drowning (Penguin Random House Canada, 2024).

Marc Perez

Early in my writing journey, a poet encouraged me to write at least five poems that related to each other. This helped me to see the ways my poems resonated with each other, which has made the initial steps in compiling a chapbook or a full-length collection less daunting. At times, I became intentional when starting a poem. It also allowed me to see patterns and trajectories in my work. Marc Perez is the author of the poetry collection Dayo (Brick Books, 2024).

Angela Sterritt

“Don’t be afraid to break the rules,” I often tell new writers. When I first started to craft Unbroken, few could understand my ambition to write a work that was part memoir and part investigative journalism. “Is there a model for the type of book you endeavor to write?” They’d ask. There wasn’t. Telling the stories of family members of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and their search for justice was my priority. But I also had my own story to tell, one of survival against all odds. Journalists didn’t understand it, some in the literary world rejected it, and even I was apprehensive about sharing my very personal story. And those weren’t the only mountains I had to climb. As an Indigenous journalist exposing the harms of a colonial institution that I was part of—the media—I was disrupting a sacred catechism of the industry. Journalists aren’t supposed to make ourselves a part of the story; we don’t naval gaze. But hard truths often come [from] within. The path towards change in this country requires reckoning with the truth and the courage to transgress limiting beliefs and rules. Fortunately, my literary agent (Samantha Haywood) and editor at Greystone Books (Jennifer Croll) saw my vision and encouraged me not to alter it but to grow it, knowing my book had a place in the world. Ultimately, since its release, Unbroken became an instant national bestseller, and the “genre-bending” book was one of its greatest appeals. Angela Sterritt is the author of Unbroken (Greystone Books, 2024).

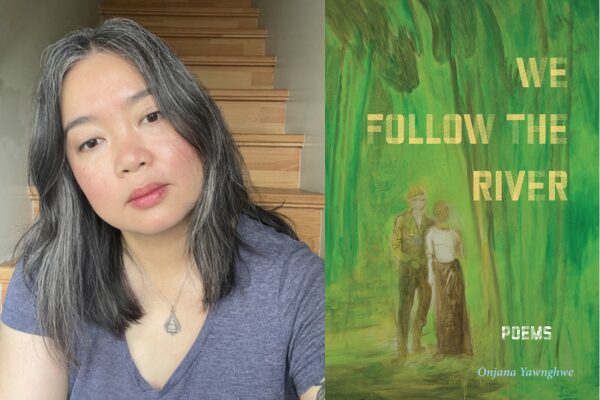

Onjana Yawnghwe

The first draft is never the final draft. Revise, revise, revise.When I was starting out writing, I had the self-confidence of a baby—insistent, aware of her own needs, with an inarticulate animal instinct. Consequently, I thought everything that came out of my head was the greatest thing ever. But a stubbornness mixed with self-confidence can lead to an alarming grandiosity that can result in tragic, subpar writing. I showed my work to friends and writers who would point out things that needed changing, and I would argue with them and stupidly stick to my own opinion. A couple of my writing teachers emphasized the importance of revision, but I didn’t believe them. The thing is, that initial euphoria in writing a first draft goes away quickly, and is soon replaced by depression and doubt. But I learned to put away the work when the bad feelings arrive and take a break. To view it with new eyes. Make changes. Add or subtract words. Do it over again. Do this until the piece tells you somehow that it is done. Onjana Yawnghwe is the author of We Follow The River (Caitlin Press, 2024).